Glacier National Park

I had heard Hole in the Wall Campground was among the nicest and most scenic in the park. And since this park is Glacier National Park, you can bet it’s worth the effort to get there. There are more than 1 million acres in Glacier National Park and not a one of them is anything but jaw-dropping gorgeous. In that 1 million acres are more than 150 named peaks higher than 8,000 feet, 131 named lakes and more than 700 miles of hiking trails to connect them all. The sheer density of peaks and the large, pristine lakes render the 14- or 15-hour drive from Grand Junction to Glacier easily worth it. It is a hiker’s paradise, a backpacker’s wonderland and a climber’s playpen. The original plan was to split our hiking group to start at opposite ends of a long scenic loop. One group would leave from Bowman Lake, the other from Kintla Lake. Each group would canoe the long lakes (seven miles in the case of Bowman Lake), then hike from there to Hole in the Wall campground. At Hole in the Wall, we’d swap car keys and each continue our hikes in opposite directions, thus avoiding pre-trip car shuttles. This sounded like fun and an interesting take on dealing with a loop hike and car shuttles, but some in this group of old friends don’t get to see each other very often. We opted for the more social up and back version of a hike to Hole in the Wall. A trail runs along the bank of Bowman Lake for all of the seven miles to the Bowman Lake campground for those who would like to hike, but we opted to canoe. Most in the group had never combined a canoe trip with a hiking trip, so half the adventure would be in traveling by boat to start the trip. Little did we know what trip organizer Dan Stone had in store. We picked September for the supposedly warm, clear days that typify that month in the Glacier area. We arrived at Stone’s house, a few hours south of Glacier, to steady rain. On the agenda that evening was tromping around Stone’s wooded property in the rain looking for two long poles we could use to lash three canoes together. Stone’s plan was to lash the canoes together and use one small outboard motor to race us across Bowman Lake. This blatant use of petrochemicals and spark plugs flew in the face of what some of us would consider a wilderness trip, but we had to admit it sounded sort of fun, and cutting poles in the forest to use in “building” our boat had an element of “adapt and innovate” that appealed to us. A backcountry trip in Glacier takes planning. Backcountry permits must be applied for months in advance and there is no guarantee of getting one. First stop for any trip is the Apgar Ranger Station at the south end of splendid Lake McDonald to pay the necessary fees, pick up the permit and watch the mandatory grizzly bear video. Bears. They call Glacier home. Hiking in Glacier is to hike with Griz. Because bear evidence is common and prevalent while hiking in Glacier, the thought of bears is never far from one’s mind. How fantastic would it be to see a grizzly bear? Or maybe not. Perhaps from a distance. It is mandatory for all hikers to carry bear spray when in the back country. We saw at least one hiker with a gun, but statistics clearly show that bear spray is far superior protection than a gun. Bears, black bears and grizzly, are out there, so safety precautions need to be taken, but bears are not a good reason to stay home. According to statistics compiled by Backpacker Magazine, there have been 27 fatal bear attacks in North America since 2000, resulting in 29 deaths. Of those,15 were in Canada, three were in Alaska, two were in Tennessee, and single fatal attacks happened in New York, New Mexico, California, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Utah and Montana. Black bears were responsible for 17 of those attacks, grizzlies accounted for 10. The average is three fatalities a year out of the millions of people who travel in the backcountry each year or who live in or near bear habitat. Backpacker reports that 26 people are killed each year by dogs. Some 90 fatalities are attributed to lightning each year. Because of the bears, all overnight backcountry travelers are required to camp in designated campgrounds. Each campground has a communal cooking and eating area and poles to hang food. These kitchens are away from tent sites. The idea is to keep all food or anything that might be of interest to a bear in a bag hung high on a pole in the kitchen. Nothing of interest to a bear should be in or around the tents. The thinking is even if a bear happens to wander in to camp, it will be more interested in the kitchen than a tent site. And if food is always out of reach, bears will learn there is no reward for visiting a campground and stay away. We arrived at the Bowman Lake boat launch a charmed group. The on and off rain of the morning gave way to bluebird skies. Spirits soared as we gaped at the scenery. We lined up our canoes, lashed on the two poles and stood back to admire our tri-canoe. We impressed ourselves with our newfound nautical design skills. The boat was stable and ran true. We loaded up and launched. While the outboard was a little too loud to talk amongst ourselves comfortably, and emitted a slight but offensive exhaust smell, cruising across spectacular Bowman Lake under crystal skies with good friends was nothing less than sublime. In a little more than one hour we cruised the seven miles to the opposite end of Bowman Lake and our first night’s camp. Because of how camps in Glacier are set up, the campgrounds are very social. Everybody ends up together in the kitchen area. There probably are people who prefer to be alone at these camp kitchens, but we didn’t meet any. We gregariously introduced ourselves to one and all. We shared food. We shared drinks. We shared laughs and the company of kindred spirits in a mountain paradise. Stone had prepared well by bringing along extra appetizers and drinks to share with the folks he knew we would meet at camp. We had a boat for this camp, remember, so weight was no issue on day one. Be prepared to interact socially with other hikers in Glacier camps and you will be richly rewarded with good company. While weight was no issue on the first day, all that changed as we pared down gear for the backpack into Hole in the Wall campground the next morning. The good times kept rolling as we hit the trail first for the summit of Brown Pass, and eventually on to Hole in the Wall. The mandatory bear movie we watched prior to our trip indicated that talking on the trail is a good way to avoid surprising bears. We were in no danger of surprising a bear or any other creature. All six of us seemed to be talking at once. The weather was glorious, the scenery divine and the company terrific. We kept up a steady din of conversation most of the morning until the gradient of the trail steepened as Brown Pass got serious. The combination of a steep, switchbacking trail and hot mid-day sun beating down combined to quiet us down as each settled into a slog up Brown Pass. The trail was hot and steep, but the scenery spectacular. Boulder Peak jutted skyward, adorned with the Hole in the Wall waterfall of many hundreds of feet. It was a walk through a picture postcard. We lunched at the Summit of Brown Pass at the base of Chapman Peak. From there we could see and Mt. Cleveland, 10,466 feet and the highest in the park. Mt. Cleveland is one of six peaks higher than 10,000 feet in the park. From Brown Pass one can hike down to the Goat Haunt area of the park and world famous Waterton Lake, where one can board a boat and cruise into Canada. The adjacent Waterton Park in Canada was combined with Glacier National Park in 1932 to form the world’s first cross-border park called Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. The park recognizes the long-held friendship between the U.S. and Canada but was also established in recognition that the geology, wildlife and general ecosystem is not affected by an international border. Together, the two parks total 1,720 square miles. It is the first international peace park ever developed of the 170 now in place around the globe. Over lunch at the top of Brown Pass, we did what many do in Glacier. We sat and discussed ideas for more trips. Driving to Waterton Park and staying in the famed Prince of Wales Hotel would be fun, we agreed. Then we could take the boat across Waterton Lake to the trailheads at Goat Haunt and fit in some backpacking before going back to the hotel. So many options are available to the hiker in Glacier that this sort of discussion could go on forever. Just because lunch was at the top of Brown Pass doesn’t mean its all down hill from there to Hole in the Wall. To the contrary, the trail climbs higher to the cirque that houses Hole in the Wall. The climb is worth it as the trail clings to the side of steep slopes. At the camp, Thunderbird Peak rises from across the valley looking like a Sentinel for all who camp at Hole in the Wall. Our dinner companions that night were four park rangers who arrived to make some repairs to the pit toilet outhouse and to study what might be called camp sprawl. They were a good-natured group, if not a bit clouded in park bureaucracy. The weather was holding steady and gorgeous. Plans were made to climb Boulder Peak the next day. Climbing Boulder Peak involves hiking the trail to the top of Boulder Pass before peeling off to pick a route up the step grass slopes to the summit. The Boulder Pass trail is worth the price of admission all by itself. It is another of Glacier’s spectacular trails. And, as you can guess, the sights from the summit of any peak in Glacier are an eye-popping view of hundreds of more peaks all around. It was possible to take in this view from a large stone throne built out of the slate-like rocks on the summit. We don’t know the full story of this throne. It didn’t insult our sensibilities, and struck us as rather clever, in fact, but in reporting its existence to one of the rangers, she expressed chagrin that this non-natural throne keeps appearing on the summit of Boulder Peak, even after she herself had previously dismantled it and scattered the rocks. Some in the group stopped to swim in the glacier-fed lakes on the way down to wash off the trail-dust of three days. I chose the natural waterfall shower conveniently flowing just below camp. This camp cannot be improved upon. Day four was the hike back to the head of Bowman Lake. Some in our group took the time and effort to climb Chapman Peak on the way down. We arrived back at the Bowman Lake camp where we had stashed provisions. Stone set about preparing his appetizers and drinks for our group and other campers. We ate well, enjoyed the company of new friends, built a fire and talked long into the night under the stars. Tomorrow we would re-build our tri-canoe and motor back to vehicles and civilization. We stayed up late that night. Nobody wanted this trip to end.

Add some text, Yo! Click this text box to change the text, style, color and fonts.

by Doug Freed

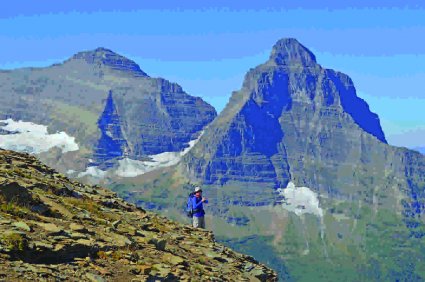

I had heard Hole in the Wall Campground was among the nicest and most scenic in the park. And since this park is Glacier National Park, you can bet it’s worth the effort to get there.

There are more than 1 million acres in Glacier National Park and not a one of them is anything but jaw-dropping gorgeous. In that 1 million acres are more than 150 named peaks higher than 8,000 feet, 131 named lakes and more than 700 miles of hiking trails to connect them all. The sheer density of peaks and the large, pristine lakes render the 14- or 15-hour drive from Grand Junction to Glacier easily worth it. It is a hiker’s paradise, a backpacker’s wonderland and a climber’s playpen.

The original plan was to split our hiking group to start at opposite ends of a long scenic loop. One group would leave from Bowman Lake, the other from Kintla Lake. Each group would canoe the long lakes (seven miles in the case of Bowman Lake), then hike from there to Hole in the Wall campground. At Hole in the Wall, we’d swap car keys and each continue our hikes in opposite directions, thus avoiding pre-trip car shuttles.

This sounded like fun and an interesting take on dealing with a loop hike and car shuttles, but some in this group of old friends don’t get to see each other very often. We opted for the more social up and back version of a hike to Hole in the Wall.

A trail runs along the bank of Bowman Lake for all of the seven miles to the Bowman Lake campground for those who would like to hike, but we opted to canoe. Most in the group had never combined a canoe trip with a hiking trip, so half the adventure would be in traveling by boat to start the trip. Little did we know what trip organizer Dan Stone had in store.

We picked September for the supposedly warm, clear days that typify that month in the Glacier area. We arrived at Stone’s house, a few hours south of Glacier, to steady rain. On the agenda that evening was tromping around Stone’s wooded property in the rain looking for two long poles we could use to lash three canoes together. Stone’s plan was to lash the canoes together and use one small outboard motor to race us across Bowman Lake. This blatant use of petrochemicals and spark plugs flew in the face of what some of us would consider a wilderness trip, but we had to admit it sounded sort of fun, and cutting poles in the forest to use in “building” our boat had an element of “adapt and innovate” that appealed to us.

A backcountry trip in Glacier takes planning. Backcountry permits must be applied for months in advance and there is no guarantee of getting one. First stop for any trip is the Apgar Ranger Station at the south end of splendid Lake McDonald to pay the necessary fees, pick up the permit and watch the mandatory grizzly bear video.

Bears. They call Glacier home. Hiking in Glacier is to hike with Griz. Because bear evidence is common and prevalent while hiking in Glacier, the thought of bears is never far from one’s mind. How fantastic would it be to see a grizzly bear? Or maybe not. Perhaps from a distance. It is mandatory for all hikers to carry bear spray when in the back country. We saw at least one hiker with a gun, but statistics clearly show that bear spray is far superior protection than a gun.

Bears, black bears and grizzly, are out there, so safety precautions need to be taken, but bears are not a good reason to stay home. According to statistics compiled by Backpacker Magazine, there have been 27 fatal bear attacks in North America since 2000, resulting in 29 deaths. Of those,15 were in Canada, three were in Alaska, two were in Tennessee, and single fatal attacks happened in New York, New Mexico, California, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Utah and Montana. Black bears were responsible for 17 of those attacks, grizzlies accounted for 10. The average is three fatalities a year out of the millions of people who travel in the backcountry each year or who live in or near bear habitat. Backpacker reports that 26 people are killed each year by dogs. Some 90 fatalities are attributed to lightning each year.

Because of the bears, all overnight backcountry travelers are required to camp in designated campgrounds. Each campground has a communal cooking and eating area and poles to hang food. These kitchens are away from tent sites. The idea is to keep all food or anything that might be of interest to a bear in a bag hung high on a pole in the kitchen. Nothing of interest to a bear should be in or around the tents. The thinking is even if a bear happens to wander in to camp, it will be more interested in the kitchen than a tent site. And if food is always out of reach, bears will learn there is no reward for visiting a campground and stay away.

We arrived at the Bowman Lake boat launch a charmed group. The on and off rain of the morning gave way to bluebird skies. Spirits soared as we gaped at the scenery. We lined up our canoes, lashed on the two poles and stood back to admire our tri-canoe. We impressed ourselves with our newfound nautical design skills. The boat was stable and ran true. We loaded up and launched. While the outboard was a little too loud to talk amongst ourselves comfortably, and emitted a slight but offensive exhaust smell, cruising across spectacular Bowman Lake under crystal skies with good friends was nothing less than sublime. In a little more than one hour we cruised the seven miles to the opposite end of Bowman Lake and our first night’s camp.

Because of how camps in Glacier are set up, the campgrounds are very social. Everybody ends up together in the kitchen area. There probably are people who prefer to be alone at these camp kitchens, but we didn’t meet any. We gregariously introduced ourselves to one and all. We shared food. We shared drinks. We shared laughs and the company of kindred spirits in a mountain paradise. Stone had prepared well by bringing along extra appetizers and drinks to share with the folks he knew we would meet at camp. We had a boat for this camp, remember, so weight was no issue on day one. Be prepared to interact socially with other hikers in Glacier camps and you will be richly rewarded with good company.

While weight was no issue on the first day, all that changed as we pared down gear for the backpack into Hole in the Wall campground the next morning. The good times kept rolling as we hit the trail first for the summit of Brown Pass, and eventually on to Hole in the Wall. The mandatory bear movie we watched prior to our trip indicated that talking on the trail is a good way to avoid surprising bears. We were in no danger of surprising a bear or any other creature. All six of us seemed to be talking at once. The weather was glorious, the scenery divine and the company terrific. We kept up a steady din of conversation most of the morning until the gradient of the trail steepened as Brown Pass got serious. The combination of a steep, switchbacking trail and hot mid-day sun beating down combined to quiet us down as each settled into a slog up Brown Pass.

The trail was hot and steep, but the scenery spectacular. Boulder Peak jutted skyward, adorned with the Hole in the Wall waterfall of many hundreds of feet. It was a walk through a picture postcard. We lunched at the Summit of Brown Pass at the base of Chapman Peak. From there we could see and Mt. Cleveland, 10,466 feet and the highest in the park. Mt. Cleveland is one of six peaks higher than 10,000 feet in the park.

From Brown Pass one can hike down to the Goat Haunt area of the park and world famous Waterton Lake, where one can board a boat and cruise into Canada. The adjacent Waterton Park in Canada was combined with Glacier National Park in 1932 to form the world’s first cross-border park called Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. The park recognizes the long-held friendship between the U.S. and Canada but was also established in recognition that the geology, wildlife and general ecosystem is not affected by an international border. Together, the two parks total 1,720 square miles. It is the first international peace park ever developed of the 170 now in place around the globe.

Over lunch at the top of Brown Pass, we did what many do in Glacier. We sat and discussed ideas for more trips. Driving to Waterton Park and staying in the famed Prince of Wales Hotel would be fun, we agreed. Then we could take the boat across Waterton Lake to the trailheads at Goat Haunt and fit in some backpacking before going back to the hotel. So many options are available to the hiker in Glacier that this sort of discussion could go on forever.

Just because lunch was at the top of Brown Pass doesn’t mean its all down hill from there to Hole in the Wall. To the contrary, the trail climbs higher to the cirque that houses Hole in the Wall. The climb is worth it as the trail clings to the side of steep slopes. At the camp, Thunderbird Peak rises from across the valley looking like a Sentinel for all who camp at Hole in the Wall.

Our dinner companions that night were four park rangers who arrived to make some repairs to the pit toilet outhouse and to study what might be called camp sprawl. They were a good-natured group, if not a bit clouded in park bureaucracy. The weather was holding steady and gorgeous. Plans were made to climb Boulder Peak the next day.

Climbing Boulder Peak involves hiking the trail to the top of Boulder Pass before peeling off to pick a route up the step grass slopes to the summit. The Boulder Pass trail is worth the price of admission all by itself. It is another of Glacier’s spectacular trails. The sights from the summit of any peak in Glacier are an eye-popping view of hundreds of more peaks all around. It was possible to take in this view from a large stone throne built out of the slate-like rocks on the summit. We don’t know the full story of this throne. It didn’t insult our sensibilities, and struck us as rather clever, in fact, but in reporting its existence to one of the rangers, she expressed chagrin that this non-natural throne keeps appearing on the summit of Boulder Peak, even after she herself had previously dismantled it and scattered the rocks.

Some in the group stopped to swim in the glacier-fed lakes on the way down to wash off the trail-dust of three days. I chose the natural waterfall shower conveniently flowing just below camp. This camp cannot be improved upon.

Day four was the hike back to the head of Bowman Lake. Some in our group took the time and effort to climb Chapman Peak on the way down. We arrived back at the Bowman Lake camp where we had stashed provisions. Stone set about preparing his appetizers and drinks for our group and other campers. We ate well, enjoyed the company of new friends, built a fire and talked long into the night under the stars. Tomorrow we would re-build our tri-canoe and motor back to vehicles and civilization. We stayed up late that night. Nobody wanted this trip to end.

I had heard Hole in the Wall Campground was among the nicest and most scenic in the park. And since this park is Glacier National Park, you can bet it’s worth the effort to get there.

There are more than 1 million acres in Glacier National Park and not a one of them is anything but jaw-dropping gorgeous. In that 1 million acres are more than 150 named peaks higher than 8,000 feet, 131 named lakes and more than 700 miles of hiking trails to connect them all. The sheer density of peaks and the large, pristine lakes render the 14- or 15-hour drive from Grand Junction to Glacier easily worth it. It is a hiker’s paradise, a backpacker’s wonderland and a climber’s playpen.

The original plan was to split our hiking group to start at opposite ends of a long scenic loop. One group would leave from Bowman Lake, the other from Kintla Lake. Each group would canoe the long lakes (seven miles in the case of Bowman Lake), then hike from there to Hole in the Wall campground. At Hole in the Wall, we’d swap car keys and each continue our hikes in opposite directions, thus avoiding pre-trip car shuttles.

This sounded like fun and an interesting take on dealing with a loop hike and car shuttles, but some in this group of old friends don’t get to see each other very often. We opted for the more social up and back version of a hike to Hole in the Wall.

A trail runs along the bank of Bowman Lake for all of the seven miles to the Bowman Lake campground for those who would like to hike, but we opted to canoe. Most in the group had never combined a canoe trip with a hiking trip, so half the adventure would be in traveling by boat to start the trip. Little did we know what trip organizer Dan Stone had in store.

We picked September for the supposedly warm, clear days that typify that month in the Glacier area. We arrived at Stone’s house, a few hours south of Glacier, to steady rain. On the agenda that evening was tromping around Stone’s wooded property in the rain looking for two long poles we could use to lash three canoes together. Stone’s plan was to lash the canoes together and use one small outboard motor to race us across Bowman Lake. This blatant use of petrochemicals and spark plugs flew in the face of what some of us would consider a wilderness trip, but we had to admit it sounded sort of fun, and cutting poles in the forest to use in “building” our boat had an element of “adapt and innovate” that appealed to us.

A backcountry trip in Glacier takes planning. Backcountry permits must be applied for months in advance and there is no guarantee of getting one. First stop for any trip is the Apgar Ranger Station at the south end of splendid Lake McDonald to pay the necessary fees, pick up the permit and watch the mandatory grizzly bear video.

Bears. They call Glacier home. Hiking in Glacier is to hike with Griz. Because bear evidence is common and prevalent while hiking in Glacier, the thought of bears is never far from one’s mind. How fantastic would it be to see a grizzly bear? Or maybe not. Perhaps from a distance. It is mandatory for all hikers to carry bear spray when in the back country. We saw at least one hiker with a gun, but statistics clearly show that bear spray is far superior protection than a gun.

Bears, black bears and grizzly, are out there, so safety precautions need to be taken, but bears are not a good reason to stay home. According to statistics compiled by Backpacker Magazine, there have been 27 fatal bear attacks in North America since 2000, resulting in 29 deaths. Of those,15 were in Canada, three were in Alaska, two were in Tennessee, and single fatal attacks happened in New York, New Mexico, California, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Utah and Montana. Black bears were responsible for 17 of those attacks, grizzlies accounted for 10. The average is three fatalities a year out of the millions of people who travel in the backcountry each year or who live in or near bear habitat. Backpacker reports that 26 people are killed each year by dogs. Some 90 fatalities are attributed to lightning each year.

Because of the bears, all overnight backcountry travelers are required to camp in designated campgrounds. Each campground has a communal cooking and eating area and poles to hang food. These kitchens are away from tent sites. The idea is to keep all food or anything that might be of interest to a bear in a bag hung high on a pole in the kitchen. Nothing of interest to a bear should be in or around the tents. The thinking is even if a bear happens to wander in to camp, it will be more interested in the kitchen than a tent site. And if food is always out of reach, bears will learn there is no reward for visiting a campground and stay away.

We arrived at the Bowman Lake boat launch a charmed group. The on and off rain of the morning gave way to bluebird skies. Spirits soared as we gaped at the scenery. We lined up our canoes, lashed on the two poles and stood back to admire our tri-canoe. We impressed ourselves with our newfound nautical design skills. The boat was stable and ran true. We loaded up and launched. While the outboard was a little too loud to talk amongst ourselves comfortably, and emitted a slight but offensive exhaust smell, cruising across spectacular Bowman Lake under crystal skies with good friends was nothing less than sublime. In a little more than one hour we cruised the seven miles to the opposite end of Bowman Lake and our first night’s camp.

Because of how camps in Glacier are set up, the campgrounds are very social. Everybody ends up together in the kitchen area. There probably are people who prefer to be alone at these camp kitchens, but we didn’t meet any. We gregariously introduced ourselves to one and all. We shared food. We shared drinks. We shared laughs and the company of kindred spirits in a mountain paradise. Stone had prepared well by bringing along extra appetizers and drinks to share with the folks he knew we would meet at camp. We had a boat for this camp, remember, so weight was no issue on day one. Be prepared to interact socially with other hikers in Glacier camps and you will be richly rewarded with good company.

While weight was no issue on the first day, all that changed as we pared down gear for the backpack into Hole in the Wall campground the next morning. The good times kept rolling as we hit the trail first for the summit of Brown Pass, and eventually on to Hole in the Wall. The mandatory bear movie we watched prior to our trip indicated that talking on the trail is a good way to avoid surprising bears. We were in no danger of surprising a bear or any other creature. All six of us seemed to be talking at once. The weather was glorious, the scenery divine and the company terrific. We kept up a steady din of conversation most of the morning until the gradient of the trail steepened as Brown Pass got serious. The combination of a steep, switchbacking trail and hot mid-day sun beating down combined to quiet us down as each settled into a slog up Brown Pass.

The trail was hot and steep, but the scenery spectacular. Boulder Peak jutted skyward, adorned with the Hole in the Wall waterfall of many hundreds of feet. It was a walk through a picture postcard. We lunched at the Summit of Brown Pass at the base of Chapman Peak. From there we could see and Mt. Cleveland, 10,466 feet and the highest in the park. Mt. Cleveland is one of six peaks higher than 10,000 feet in the park.

From Brown Pass one can hike down to the Goat Haunt area of the park and world famous Waterton Lake, where one can board a boat and cruise into Canada. The adjacent Waterton Park in Canada was combined with Glacier National Park in 1932 to form the world’s first cross-border park called Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. The park recognizes the long-held friendship between the U.S. and Canada but was also established in recognition that the geology, wildlife and general ecosystem is not affected by an international border. Together, the two parks total 1,720 square miles. It is the first international peace park ever developed of the 170 now in place around the globe.

Over lunch at the top of Brown Pass, we did what many do in Glacier. We sat and discussed ideas for more trips. Driving to Waterton Park and staying in the famed Prince of Wales Hotel would be fun, we agreed. Then we could take the boat across Waterton Lake to the trailheads at Goat Haunt and fit in some backpacking before going back to the hotel. So many options are available to the hiker in Glacier that this sort of discussion could go on forever.

Just because lunch was at the top of Brown Pass doesn’t mean its all down hill from there to Hole in the Wall. To the contrary, the trail climbs higher to the cirque that houses Hole in the Wall. The climb is worth it as the trail clings to the side of steep slopes. At the camp, Thunderbird Peak rises from across the valley looking like a Sentinel for all who camp at Hole in the Wall.

Our dinner companions that night were four park rangers who arrived to make some repairs to the pit toilet outhouse and to study what might be called camp sprawl. They were a good-natured group, if not a bit clouded in park bureaucracy. The weather was holding steady and gorgeous. Plans were made to climb Boulder Peak the next day.

Climbing Boulder Peak involves hiking the trail to the top of Boulder Pass before peeling off to pick a route up the step grass slopes to the summit. The Boulder Pass trail is worth the price of admission all by itself. It is another of Glacier’s spectacular trails. The sights from the summit of any peak in Glacier are an eye-popping view of hundreds of more peaks all around. It was possible to take in this view from a large stone throne built out of the slate-like rocks on the summit. We don’t know the full story of this throne. It didn’t insult our sensibilities, and struck us as rather clever, in fact, but in reporting its existence to one of the rangers, she expressed chagrin that this non-natural throne keeps appearing on the summit of Boulder Peak, even after she herself had previously dismantled it and scattered the rocks.

Some in the group stopped to swim in the glacier-fed lakes on the way down to wash off the trail-dust of three days. I chose the natural waterfall shower conveniently flowing just below camp. This camp cannot be improved upon.

Day four was the hike back to the head of Bowman Lake. Some in our group took the time and effort to climb Chapman Peak on the way down. We arrived back at the Bowman Lake camp where we had stashed provisions. Stone set about preparing his appetizers and drinks for our group and other campers. We ate well, enjoyed the company of new friends, built a fire and talked long into the night under the stars. Tomorrow we would re-build our tri-canoe and motor back to vehicles and civilization. We stayed up late that night. Nobody wanted this trip to end.

Back Next

Magazine Posts

Magazine Posts Table of Contents

Table of Contents