Hooty Help

Hooty Help

Hatchery Rearing: Natural Selection Vs. Fecundity Selection

Posted

|

Views: 1,072

Hatchery Rearing: Natural Selection Vs. Fecundity Selection

One Chinook Salmon’s Point of View

As a femifish—who, mind you, has not once felt in need of any bicycle—I find myself personally involved with the captive breeding debate. I have al-ways been a proponent of great minds like Globefish Steinem and Bell Fishhooks; I have always supported the idea that a fishes body is hers, and that she alone should possess control over it. Contrary to popular opinion, I have never doubted that I do, in fact, have a backbone. But with age comes wisdom, as well as a deeper responsibility towards my own school of fish—a broader purpose, perhaps. It is here that I am catapulted into deciphering the semantics of my own own personal dilemma on the subject of hatchery rearing.

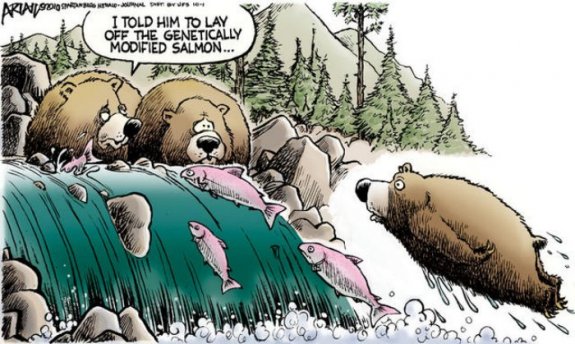

Humans, sure. They think captive breeding programs are great. They “love” salmon. Grilled, seared, baked, breaded—you name it. Ten years ago when sushi really started to take off, did you hear me complain? This hatchery rearing, however, is a different story. Humans really think that these programs increase the Chinook preservation—and honestly, with that I can get down (for a fish who swims upstream). Scientists are using these programs to supplement populations that are declining, and to help our little fry grow up into strong anadromous fish with tons of Omega-3s. However, we need to figure out a middle ground, on which scientists can help us maintain our population sizes, without discouraging maladaptive traits.

You see, the genetic implications are what worry me about captive breeding programs. Not only are our eggs being taken from us involuntarily, but this is actually starting to throw off the equilibrium of our unique Chi-nook traits. Scientists are conducting studies about how fecundity selection is promoting unnaturally small salmon eggs, when in the wild, natural selec-tion favors large eggs. The “catch” is that unintentional selection in captivity can lead to rapid-changes in our critical life-history traits, thus reducing the success of reintroducing such salmon back into nature.

As a femifish—who, mind you, has not once felt in need of any bicycle—I find myself personally involved with the captive breeding debate. I have always been a proponent of great minds like Globefish Steinem and Bell Fishhooks; I have always supported the idea that a fishes body is hers, and that she alone should possess control over it. Contrary to popular opinion, I have never doubted that I do, in fact, have a backbone. But with age comes wisdom, as well as a deeper responsibility towards one's own school of fish—a broader purpose, perhaps.

It is here that I am forced to decipher the semantics of my own own personal dilemma on the subject of hatchery rearing.

Humans, sure. They think captive breeding programs are great. They “love” salmon. Grilled, seared, baked, breaded—you name it. Ten years ago when sushi really started to take off, did you hear me complain? Never. This hatchery rearing thing is a different story. Humans really think that these programs increase the preservation of my species—and honestly, I can get down with that (for a fish who swims upstream).

OP-ED ON Hatchery Rearing: Natural Selection Vs. Fecundity Selection

One Chinook Salmon's Point of View

But the common misunderstanding is that these reintroduction programs do only good. It's true that scientists are using these programs to supplement declining populations, and to help our little fry grow up into strong anadromous fish with tons of Omega-3s. However, we need to figure out a middle ground, on which scientists can help us maintain our population sizes, without encouraging maladaptive traits.

(Traits that become more harmful than helpful; in other words, the stark opposite of adaptations that we have spent hundreds of thousands of years acquiring)!

You see, the genetic implications are what worry me about captive breeding programs. Not only are our eggs being taken from us involuntarily, but this is actually starting to throw off the equilibrium of our unique Chinook traits. Scientists are conducting studies about how fecundity selection is promoting unnaturally small salmon eggs, when in

By Simone de Salmon

the wild, natural selection favors larger eggs.

[Fecundity selection is the process by which differential reproductive success among individuals in a population is the result of phenotypic traits that contribute to the production of a higher number of offspring per reproductive episode. The theory was coined by the human Charles Darwin in 1869.]

Heath, Daniel D. “Rapid Evolution of Egg Size in Captive Salmon.” Science Magazine. (March 2003): 1738-40. University of Windsor. Web. 11 April 2016.

Magazine Posts

Magazine Posts Table of Contents

Table of Contents